Gentle Reader,

The idea of a prescription is much beloved of modern society. Take three tablets daily, after meals, and the illness will soon be cured. Simple guidelines like this, infused with the sanitary blessing of medicalised language, reassure the sick patient that all is under control.

The desire for prescriptions extends beyond the medical realm. We all want a rulebook or a playbook, a modus operandi for how to navigate the world.

We want step-by-step instructions, hacks, and tricks. Many people even follow a recipe or prescription for their entire life. Here is an example. This recipe is called ‘How to be conventionally successful.’

Attend school

Graduate with good results

Study Law or Medicine

Find a partner from your chosen field.

Get a job and climb the ranks

Buy a big house and have 2.4 kids

Raise kids, keep working.

Buy a bigger house so that your grandkids can visit.

Enjoy your retirement

There is nothing wrong with this life; it is simply a common prescription for success.

Why recipes and prescriptions fail

1. They are too generic

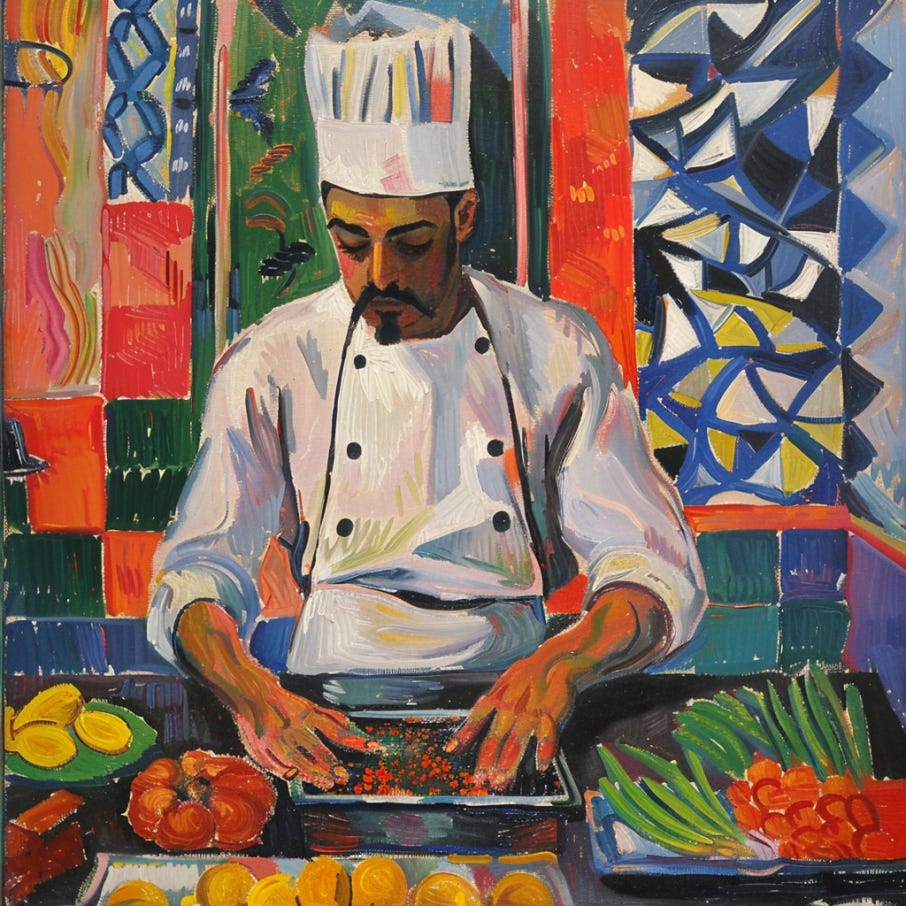

I used to wonder about how one chef could be famous, and another not good. Was it not true that the world contains a set number of recipes? In this case, if I follow a Gordon Ramsay recipe, won’t I be able to produce the same result as him?

And yet, many recipes later, many iterations of burned garlic and carbonara that resembles scrambled eggs, of dry chicken and oppressive stews, I have found this not to be the case.

Why?

Recently, I spoke to a woman who is training to become a baker. Such training takes many years, and involves going to different bakeries around France. Part of this training had also brought her to Ireland. I asked her why Irish bread is not as good as French bread.

She told me that it was because French flour is better than Irish flour, and that they imported their flour from France. Wait, there are different kinds of flour, different qualities?

Well, yes, apparently. Because flour comes from wheat, and wheat grows in different ways, in different climates, the effects of which affect the quality of the wheat, just as different terroirs produce different wines, and a good or a bad crop can happen any year.

Feeding this back into my recipe algorithm, I realised that this is how I would fail at the first step of a recipe. If flour is not just flour, then an idiot like me would probably use the wrong brand or type.

That won’t be my first mistake either. Cooking anything requires a certain amount of judgement, and judgement comes from a mixture of experience and intuition. For example, a recipe might say to cook something for 10 minutes, but this is secretly code for ‘this food should be ready in 10 minutes.’

But what Gordon Ramsay knows that I don’t is that food will cook at different speeds, on different stovetops, with different pans, and so this general recipe might fall short of the mark, for one who is not willing or able to adjust.

The natural consequence of the this is that a fine meal can easily turn into a charred disaster, despite supposedly following the instructions.

2. Instructions do not account for individuality

The inability to insert subtle variables into a prescription or a recipe is its downfall. A quirky kid following the conventional life recipe will probably realise its just not for him – but will he realise too soon or too late?

It’s true that recipes will work for some, but not for others. But for this latter group, they also cause a lot of harm, sending them on a misguided wild goose chase for anything from five minutes to a whole lifetime.

Many such recipes are infiltrated into our brains in childhood, and are almost indistinguishable from some innate knowledge. For example, a parent might tell their kid, both implicitly and explicitly throughout their childhood that you must have children, that you should get a steady pensionable job, that you should never buy a house with someone, that work is the most important thing in life.

This advice seeps into the developing brain. Some of it will help, some will hinder, will slow down the realisation of what we really want.

3. Prescriptions do not ask why

If a guy who was never successful with women asks for help, he will hear every kind of crazy recommendation. Some of these recommendations are given because they have worked for someone. There is always something that works for someone, somewhere.

The guy might hear:

be yourself

join a dancing class

go to nightclubs

get rich

smile

go on dating apps

Again, some of this might help. But there is, somewhere, a piece of advice for this guy which recognises why he is not good with women, and which seeks to remedy this cause, which can be complex or very simple, ranging from he needs to work on his relationship with his mother, or he needs to hit the gym, brush his teeth, practice smiling, become less selfish, figure out what he wants in life, or start leaving the house.

4. The highest performers are not legible

There are elite performers everywhere. If their outcomes were the result of following simple recipes, then we could all emulate their success, and the world would be full of elite performers.

But this is not possible, both because people have different attributes, and because what works for one person, won’t work for another.

If you ask Lionel Messi how to become the best soccer player in the world, or ask James Joyce how he wrote Ulysses, neither will have a clue. Just because Joyce stayed up late at night drinking white wine and laughing to himself while writing Finnegans Wake unfortunately doesn’t mean that you should too.

Peak performance is an emergent flow state which results from complex and innumerable interweaving factors. Recipes will never get us there, and yet that’s all we have, mixed with personal experience and bias.

An orthopaedic surgeon will tell you that your bad knee needs an operation, a physio will tell you it needs strengthening exercises, and a psychiatrist will tell you that pain and pain experience are not the same, and that you need to resolve your fear of death.

They are all right, in a way, but only one of them might be right for you, for your knee.

Temptation

The allure of the prescription is strong: it promises us that we can solve a problem without having to think in any great detail, without having to figure things out. It saves us hassle and and energy, and it explains why the best way to title your article or Youtube video is something like ‘one cool trick to…’ or ‘the 3 simple steps to…’

We just can’t resist. And yet, we must. It doesn’t mean, however, that there are not general behaviours which are not helpful for people in many situations, such as working hard, exhibiting honesty, integrity, and so on, which will lead to modicums of success. But, in order to fully reach our potential, to become our authentic, actualised selves, we must find the way forward which works for us, which is married to our skills, desires, and intuitions, whatever they may be.

Gentle reader, thank you for reading this week’s edition, which came a little later than usual. While holidays in Spain, I developed a manflu of sorts, and spent various nights flailing about in a feverdream, while sweating profusely through the cheap blankets of my hotel bed. My brain is still not functioning 100%, so please excuse any laxities or laziness of prose observed above. Besos xx.

Affiliates: I recommend the Supernote e-ink device, which I use for reading, writing, and annotating documents. This affiliate link is only valid for EU customers.

You can also support me by joining the Pathless Path Community, a cozy online space where creators support each other to work in the most meaningful and aligned way possible.

This post reminds me of “No Surprises” by Radiohead.

The challenge I often encounter is the fear of mucking it up. I fall victim to it as much as many others I know.

The antidote to the uncertainty surrounding “will it work” is a recipe. In the tea world this looks like brewing parameters (“brew like this for a perfect cup”); in life, it looks like the traditional path as you’ve described.

The recipe will produce a predictable result, even if it’s not the one we really want.

If people fear an over-brewed cup of tea, we can imagine how much more they fear messing up their life.

This is indeed a great topic. However, taken to heart, I fear that it would eliminate a third of the volumes in my local bookstore and perhaps an even greater percentage of the “best self” content on Substack.

As the great rowing coach Steve Fairbairn once wrote, each person has to find their own way to get power on the oar.