Gentle Reader,

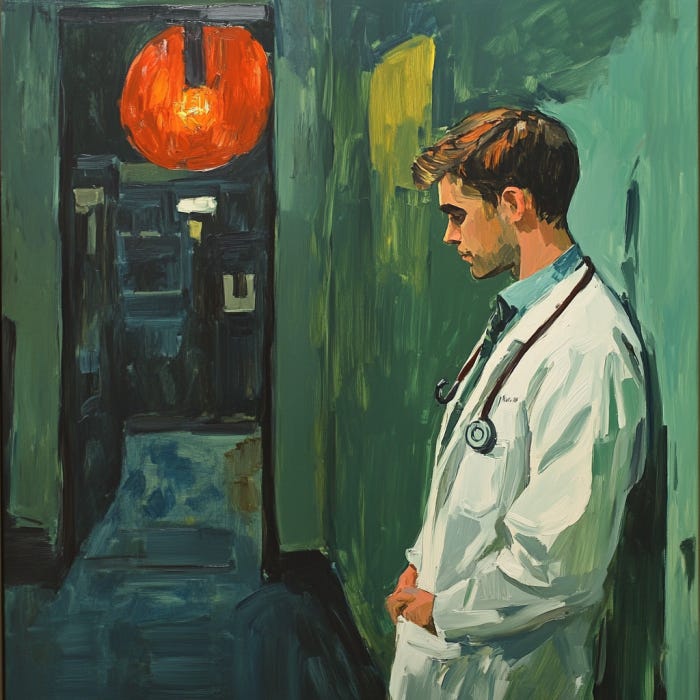

Many years ago, I was on the graveyard shift in a large hospital as a junior doctor. The hospital was eerily quiet that night, to the extent that I paged myself twice to make sure that the device was actually working – it was.

Just an oddly calm night. Unable to rest or get any sleep, I stirred myself and began to wander the wards. Usually, you would never do this, as you’re basically asking for trouble, but I couldn’t settle in my little on-call room. That was probably due to the giant telephone stuck to the wall, nine inches from the pillow, and the DECT phone which lay on my bockety bedside table, redlettered with the engraving ‘CARDIAC ARREST PHONE.’

’Such environs were not conducive to sleep, especially for a light sleeper and delicate soul like the present writer. I got up and opened the creaky door and looked down the hall of the doctors’ residence. It was lined with lockers. One or two of them, as always, vibrated occasionally with a pager (or a ‘bleep’ was we used to call them) which somebody would hastily dump before going home, forgetting to turn it off.

This was the cause of much unrest. Now and then some insomnia-addled doctor would burst out of a room, clearly on the verge of a nervous breakdown, to kick a locker. The usual course of action was to haul the whole locker unit, which wasn’t light, across to the other side of the doctors’ residence, in the hope of being able to sleep. Such scenes were not uncommon.

This job, as you are beginning to understand, was a sort of torture. If the experience of being waterboarded were instantiated a job, it would probably be the role of surgical intern in a busy Irish tertiary hospital.

But apart from that, it was grand. In any case, I had no choice, and I headed off down the corridor through the residence, swiping out through the magnetised door, and entering the hospital proper. But where to go?

The most feared ward at that time was upon on the third floor, so there was no chance I was going there. I decided to just head up to the ground floor, leaving behind the dungeon which contained the residence, radiology, and the surgical theatres.

I swung a left. The corridor was eerily bright, being completely artificially lit, and I heard the approaching hum of one of those four-wheeled floor scrubbers you only see at night. It buzzed towards me, topped by a cleaner who sat in his little bubble, headphones tucked over his ears, and staring dully straight ahead. I let him pass me and went up onto the ground floor where I entered the first ward on the right, named, like every ward, after an Irish Saint.

It was about three in the morning now, the witching hour. I shuffled along towards the staff base where I saw a nurse standing, writing in a chart. Being nosey, and imbued with a sense of boredom mixed with a sense of impending doom, I looked at the chart and saw something startling.

The odd thing was that it was an observations chart, which records the heart rates, blood pressures and temperatures, etc, of patients. What was unusual was that all of these numbers were out of kilter, to the extent that the patient was clearly exceptionally unwell.

I asked her about it, and she told me that since the patient was so sick, she called the senior registrar straight away, and bypassed me. This is actually what the protocol demanded, but it is still unusual, as usually I would have been called anyway, if not to make decisions then at least to help with the jobs which had to be done. She told me the senior doctor was in there with him now, so I wandered in behind the curtain at the end of the bay, to see if he needed help.

The man inside was middle-aged, and bearing the signs of personal neglect. He was not clean shaven and his eyes contained the misty rheum associated with those who, finding themselves confronting the world without the aid of substances, see everything all too clearly. He was also exceptionally angry, and all the tests I had to carry out on him invited criticism. When I took a blood test, I was not skilled, when I put in a catheter (admittedly an unpleasant procedure), I was too rough, when I was asked questions, I did not know the answer.

I couldn’t wait to get away from him. His general appearance, aside from the signs of neglect I mentioned, caught me by surprise, because he showed no outward signs of the deteriorating parameters which has chart captured. That was a valuable clinical lesson which put me in good standing later on, but at the time he was not short of breath, nor did he have a cough, feel tired, or have pain anywhere: odd.

After the many tests and procedures which I had to carry out on the poor man, we began to develop a rapport as such. Either his initial anger, which in hindsight was probably fear, calmed after realising I was trying to help, or else he took pity on the young and terrified junior doctor in front of him. Regardless, we began to chat and he asked me about my hobbies.

I told him I play sport, go to the gym, travel, read books.

Books? he said.

Books, I said.

The man came alive. Behind the stubble a smile twisted happily the corners of his mouth, and his eyes clarified, revealing a keen blue.

Which books?

Joyce, Proust, Hemingway, Woolf, Shakespeare…

Joyce?

Joyce, I said.

He sat up in the bed and unprompted began quoting the famous first paragraph of Joyce’s unwieldy and convoluted chef d’oeuvre, Finnegans Wake.

Riverrun, he said, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

The opening paragraph. I was impressed.

That used to be on the back of the old ten pound note, he said.

Was it? I said.

Do you remember, he said, the old ten pound note?

I did indeed remember it, but hadn’t remembered the quote. He asked me if I had ever read anything by Evelyn Waugh.

No, I said, I haven’t read her.

Her? He laughed, coming alive again.

It’s a man, he said, Evelyn Waugh was a man. A brilliant writer.

The present writer was not aware of this. I had a laugh, humbled. Eventually, I finished poking and prodding him and, leaving him, he asked for my name. Out in the corridor, the senior doc told me he was in with a brain tumour and his immune system was very weak, which explained why he deteriorated so quickly and without any sense of it himself.

It was my last night shift. I finished that morning at 7 and was back the next day at 7am. I had thought about him on my day off as one thinks of a curiosity, something unexpected; I wondered if he had any more book recommendations for me. Or maybe he wouldn’t remember me or want to see me again. After all, I wasn’t part of his treating team, only an on-call doctor who was covering his ward.

When I came to the ward that next day to check on him, I did not realise that the purple signal on the door, the triskele which signals a death, referred to him.

He had passed away. I couldn’t believe it – he had died hours after I left him. The nurse, who was also a little shaken, told me that his estranged sister had called about him to see if he was okay, and found out about his death. She said he was a very learned but difficult man, who had been living homeless for years.

It left a mark on me. I learned something that night about the human condition, about the refined and artistic souls which can inhabit bodies which, to external appearance, have renounced the world, have given up. But there is a light inside people that cannot be quenched. That man was a passionate lover of literature, something which would have been impossible to guess if you saw him on the streets under a bundle of blankets, or shaking his cup at you in a doorway.

And he was right about Evelyn Waugh.

I cannot think of Brideshead Revisted without picturing the scene of me and the man in that ward, going through the motions of our own little scene, couched in the mysterious intimacy of a death which neither of us knew was just hours away.

Edward, this was lovely.

What a piece of literature.

Yours, that is.

I was captivated by your story and hit with some powerful lessons.

Thank you, Edward.